Fracture Nomenclature for Pediatric Humeral Shaft fractures

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Pediatric Humeral Shaft Fractures, the historical and specifically named fractures include no fracture eponyms.

Fractures of the humeral shaft are relatively uncommon in children and adolescents, accounting for about 10% of all humerus fractures in this population. These injuries are frequently seen in newborns, where they occur from birth-related trauma, particularly in large infants and those in breech position. There is also a bimodal age distribution for children younger than 3 years and older than 10 years of age. In both age groups, the mechanism of injury is typically either a fall on an outstretched hand or a direct blow to the upper extremity. Sports are often responsible for humeral shaft fractures in adolescents, and these injuries may also occur from high-energy trauma, such as in a motor vehicle collision. Conservative treatment consisting of a period of immobilization is indicated in most cases, while surgery may be indicated for patients that fail conservative treatment and those with open fractures or otherwise severe injuries.1-3

Definitions

- A pediatric humeral shaft fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the pediatric humeral shaft.

- A pediatric humeral shaft fracture produces a discontinuity in the humeral shaft contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A pediatric humeral shaft fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

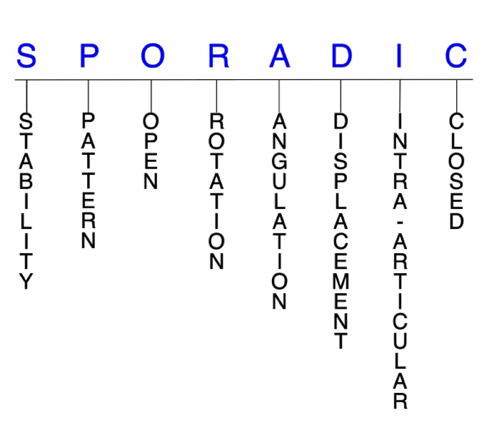

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability are not well defined in the literature.4-6

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragments’ alignment is maintained by with simple splinting or casting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and immobilization. Typical unstable pediatric humeral shaft fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

P - Pattern1,7

- Pediatric humeral shaft fractures are typically classified according to the following features:

- Anatomic position

- Distal third

- Middle third

- Proximal third

- Fracture pattern

- Presence of soft tissue damage

- Transverse and short oblique fractures generally occur secondary to direct trauma, while spiral and long oblique fractures are usually caused by indirect twisting.7

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the pediatric humeral shaft require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.4,8,9

R - Rotation

- Pediatric humeral shaft fracture deformity can be caused by proximal rotation of the fracture fragment in relation to the distal fracture fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- The degree of acceptable angulation changes based on the patient’s age. According to one age-based algorithm, 70° of angulation is acceptable for children under 5 years, 40–70° of angulation is acceptable for children aged 5–12 years, and 40° of angulation for children older than 12 years.10

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: ≥1 fracture lines defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Intra-articular fractures are those that enter a joint with ≥1 of their fracture lines.

- Pediatric humeral shaft fractures can have fragment involvement at the glenohumeral, radiocapitellar, or ulnohumeral joints.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised, and the risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.4-6

Related Anatomy11-13

- The humerus is a long bone that can be divided into a proximal end, a long shaft, and a distal end.

- The proximal end consists of an anatomic neck, the humeral head, the surgical neck, and the greater and lesser tuberosities at its proximal end. The humeral head articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula to form the glenohumeral joint.

- The humeral shaft extends distally from the proximal border of the pectoralis major insertion to the supracondylar ridge. It is nearly cylindrical in its proximal half and then becomes flattened and triangular towards its distal end. It has 3 major surfaces: the anterolateral, anteromedial, and posterior surfaces.

- At the distal end, the medial condyle articulates with the ulna to form the ulnohumeral joint and the capitellum articulates with the radial head to form the radiocapitellar joint.

- The humeral shaft serves as an insertion site for the pectoralis major, deltoid, and coracobrachialis tendons, and is the origin site for the brachialis, triceps, and brachioradialis tendons.

- Two important regions of the humeral shaft are the deltoid tuberosity and the radial groove.

- The deltoid tuberosity is an elevation near the middle of the anterolateral surface, which is the insertion point of the deltoid tendon.

- The radial groove or sulcus starts distal to the attachment of the lateral head of triceps on the posterior surface and runs distal and lateral toward the anterolateral surface. The radial nerve and profunda artery both pass within this groove.

- The radial nerve is the major nerve of the humeral shaft and is located 14 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and 20 cm proximal to the medical epicondyle. Its proximity to the humerus explains why the radial nerve can be injured in humeral shaft fractures.

Incidence

- Humeral shaft fractures account for about 1–5% of all pediatric fractures and about 10% of all pediatric humerus fractures.2,14,15

- These injuries occur most commonly at two peaks: in toddlers younger than 3 years and children older than 10 years of age.2,14

- Most common pediatric humeral shaft fractures occur in either the middle or distal third of the humerus. Concomitant radial nerve injuries occur frequently in midshaft fractures due to the close proximity of the nerve to the fracture site.3