Fracture Nomenclature for Thumb Distal Phalanx Fracture Pediatric

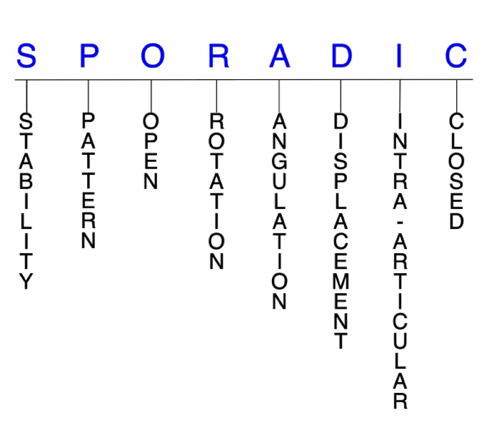

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Thumb Distal Phalanx Fracture Pediatric, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Mallet thumb fracture

Seymour thumb fracture

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

In children, more fractures occur in the hand than anywhere else in the body, and the phalanges account for the majority of these injuries. The proximal phalanx of the thumb is the most frequently fractured of these bones, followed by the distal phalanx. The pediatric thumb also ranks second behind the little finger in incidence of fractures. The cause of these injuries is largely dependent on the age of the child, with crushing accidents being more common in toddlers and sports activities being more common in older children. Although pediatric fractures share some similarities with their adult counterparts, the presence of physes and growth patterns in children and adolescents underlies the importance carefully considering when diagnosing and managing these injuries to ensure a positive outcome.1-5

Definitions

- A pediatric thumb distal phalanx fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the thumb distal phalanx.

- A pediatric thumb distal phalanx fracture produces a discontinuity in the distal phalanx contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A pediatric thumb distal phalanx fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability is not well defined in the hand surgery literature.6-8

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragment’s alignment is maintained with simple splinting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and simple splinting. Typically unstable pediatric thumb distal phalanx fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- In the pediatric population, even most displaced fractures are frequently reduced closed and often quite stable.2

P - Pattern

- Thumb distal phalanx tuft: oblique, transverse, or comminuted; tuft fractures usually result from crush injuries, are often comminuted, and are nearly always associated with an injury to the nail matrix, digit pulp, or both. Displaced fractures of the distal phalanx tuft can affect joint congruity.9,10

- Thumb distal phalanx shaft: transverse, oblique, or comminuted, with or without shortening; transverse shaft fractures are potentially unstable, as the fracture tends to angulate with its apex anterior secondary to the pull of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendon on the proximal fragment.9

- Thumb distal phalanx base: can involve the interphalangeal (IP) joint; may be intra- or extra-articular and usually involves the dorsal or volar lip of the distal phalanx base.11

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the pediatric thumb distal phalanx require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.6,12,13

- Since Seymour fractures of the thumb involve an associated nail be laceration and displacement, they are technically considered open fractures.1

R - Rotation

- Pediatric thumb distal phalanx fracture deformity can be caused by rotation of the distal fragment on the proximal fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity; this is not a common type of fracture deformity in the pediatric thumb distal phalanx but some pediatric thumb distal phalanx fractures will have substantial rotational deformities.14 Rotational deformity is difficult to detect on x-ray and should be evaluated clinically by visualizing the plane of the nail bed and the degree of tip rotation during IP joint flexion.

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- Example: Seymour fractures typically result from a volar force which causes a dorsal apex angulation of the diaphysis compared with the epiphysis.1

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: fracture line (2) defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

- Displaced epiphyseal fractures of the pediatric thumb distal phalanx can result in articular and physeal incongruity, and surgery is therefore required in many cases.15

- Most pediatric thumb distal phalanx fractures are nondisplaced, with support provided by the robust periosteum.2

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Fractures that enter a joint with one or more of their fracture lines.

- Pediatric thumb distal phalanx fractures can have fragment involvement with the IP joint.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or particularly if there is a step-off in the articular surface then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.6-8

Pediatric thumb distal phalanx fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms, and other special fractures

Mallet thumb fracture

- Mallet thumb fractures in children are somewhat similar to their equivalent injury in adults, with both typically resulting from a flexion force directed to an actively extended thumb, which hyperflexes the IP joint and damages the extensor pollicis longus' insertion (EPL); however, there are several important differences between the two injuries that are important to acknowledge:1,10,15,16

- In children, the FPL tendon inserts on the metaphysis and the EPL tendon inserts on the epiphysis of the thumb distal phalanx.15

- The physis of the thumb distal phalanx may be either still open or gradually closing in children, which usually occurs between ages 13-16.17

- In adults, mallet thumb deformities result from injury or laceration to the extensor tendon with or without an associated fracture. But in skeletally immature children, mallet thumb typically occurs as an avulsion fracture of the EPL at the distal phalangeal epiphysis, which avulses a fragment of the physis.1,16

- This avulsion results in an intra-articular fracture that may extend to or through the metaphysis of the distal phalanx. When this occurs, it should be referred to as Salter-Harris type III or IV fracture, respectively.1,10

- Soft tissue swelling is commonly noted over the dorsum of the IP joint in these injuries, and the avulsed bone fragment is dorsally displaced to a varying degree.11

- In young children, delayed diagnosis of mallet thumb is common, likely because of the rarity of this injury and the fact that functional impairment is not usually noted immediately.16

Imaging

- Posteroanterior, oblique, and lateral X-ray views are recommended to confirm the diagnosis.

- Radiographs should be obtained before active motion testing to prevent potential displacement of an avulsed fracture fragment.

- MRI may also be needed to identify a pediatric mallet thumb fracture.

Treatment

- Due to the low incidence of mallet thumb fractures, there is a lack of consensus on the optimal treatment strategy for these injuries, but treatment principles for pediatrics are generally similar to those used for adults.10,18,19

- Treatment for both open and closed mallet thumb injuries varies from splinting of the IP joint alone to operative repair with or without temporary K-wire fixation of the IP joint.

- Most experts recommend treating closed mallet thumb injuries nonsurgically with extension splinting, although there is still ongoing debate regarding this approach, and the optimal type of splint has not been identified.19,20

- Conservative treatment is also indicated for fracture fragments smaller than 30-40% of the joint surface—which are typically stable—and those with displacement of <2 mm. Fractures involving less than 30% of the joint require a long duration of the splint use and excellent patient compliance.10

- Treatment for pediatric thumb mallet fractures should include full-time splint or cast immobilization of the IP joint in full extension for 4 weeks, followed by 2-4 weeks of nighttime splinting.1 Younger children will heal faster.

- A major issue with conservatively treating mallet fractures in children is compliance with splinting, as some patients cannot maintain the splint for behavioral reasons or an improper fit. In these situations, a transarticular K-wire may need to be placed through the IP joint and the hand casted to protect the pin from breakage.2

- Surgery is indicated when conservative treatment fails, in open mallet thumb fractures, and in fractures with persistent volar subluxation, joint incongruity, or greater than 50% involvement of the joint.10,19,20

- Reduction is typically performed with percutaneous K-wire fixation and may involve multiple pins to reduce the fracture. The tendon should be repaired after the IP joint is pinned in hyperextension. The K-wire is removed at 6 weeks postoperatively, and a splint is to be worn for the next 6 weeks, followed by nighttime splinting for another 4 weeks.2,19

- Extension block pinning can also be used to percutaneously reduce and stabilize the fracture and IP joint.1,2

- Other surgical techniques include tension band wiring, hook plating, internal suturing, pin fixation, and the use of bone anchors. If the patient is near skeletal maturity, a screw, tension band, pullout wire, or suture anchor may be used for fixation.1,2

- Cases in which the proximal severed EPL tendon retracts proximal to the IP joint may also necessitate surgery at the time of presentation, since a conservative approach to management could ultimately fail.20

- Aggressive physical and/or occupational therapy should be considered in children who do not regain flexion appropriately after surgery.17

- Diagnosing and addressing these injuries early will increase the chances of a satisfactory outcome.10

Complications

- Infection

- Posttraumatic osteoarthritis

Outcomes

- Most thumb mallet fractures heal well with minimal residual problems.

Seymour thumb fracture

- A “Seymour fracture” of the thumb, as with other digits, is a Salter-Harris type I or II fracture of the distal phalanx physis with concomitant avulsion of the proximal edge of the nail from the eponychial fold, flexion deformity at the fracture site, and possible ungual subluxation. It has also been suggested that Seymour fractures can occur in a juxta-epiphyseal position, 1-2 mm distal to the physis in the metaphysis.2,21

- These are displaced fractures that typically occur from crush injuries to the distal phalanx, resulting from a volar force and the dorsal apex angulation of the diaphysis compared with the epiphysis. The commonly associated nail bed laceration makes these open fractures because the nail is avulsed and the germinal matrix is torn.1,21,22

- The distal phalanx is typically in a flexed posture as a result of the imbalance between the EPL and FPL tendons. Because of this flexed posture of the distal phalanx, a Seymour fracture of the thumb may be misinterpreted as a IP dislocation or bony mallet injury.22,23

Imaging

- Because posteroanterior X-ray views may appear normal, a lateral view of the thumb is typically needed to confirm a Seymour fracture diagnosis.

Treatment

- Since these are nearly always open injuries, optimum treatment for Seymour fractures of the thumb requires early recognition and management to prevent infection.15

- Acute treatment of open Seymour fractures requires surgical intervention and should consist of the following: nail plate removal, thorough irrigation and debridement of the fracture, gentle removal of the incarcerated nail bed from the fracture site, reduction of the fracture with or without pinning, repair of the nail bed if a substantial proximal flap exists, replacement of the nail plate underneath the eponychial fold, and splinting or casting.2

- Seymour fractures are usually unstable, and reduction should therefore be maintained by K-wire fixation. Using fluoroscopy for the passage of a fine K-wire can accomplish fixation with minimal iatrogenic damage to the epiphysis.23

- Adequate observation of the nail bed injury and the fracture site may require incising and reflecting the eponychial fold.2

- Postoperative parenteral antibiotics should also be administered, followed by a short course of oral antibiotics for approximately 5-7 days.2,22

- The rare case of a closed Seymour fracture can be managed with closed reduction and a splint; however, since children may not be compliant with splint wear, even these fractures are often managed surgically.1

Complications

- Infection

- Malunion

- Osteomyelitis

- Premature physeal closure

- Nail bed deformity

- Articular deformity

Outcomes

- In one study of 24 patients with Seymour fractures of various digits, including the thumb, 9 children had closed injuries and were treated with closed reduction and splinting using a standardized forearm-based finger splint in intrinsic-plus position. The other 15 patients underwent surgical management.

- Clinical results revealed that 23 of the 24 patients had re-established full motion in comparison with the corresponding digit of the opposite side, with a mean motion range of 80°. No infections were reported.

- At the 1-year follow-up, no patients complained of pain, and patient satisfaction was primarily good or excellent.21

Related Anatomy

- The pediatric thumb distal phalanx consists of a distal bony tuft, a narrow diaphyseal shaft, a proximal metaphysis, and a base that articulates at the IP joint with the thumb proximal phalanx. The physis is located at the base of the distal phalanx, which has a dorsal and volar lip.1,24

- The ligaments associated with the thumb distal phalanx include the joint capsule, volar plate of the IP joint, and the proper and accessory ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and radial collateral ligament (RCL), which originate from the phalangeal head, cross the physis, and insert onto the metaphysis and epiphysis of the distal phalanx. The collateral ligaments also insert onto the volar plate to create a three-sided box that protects the physis and epiphysis of the IP joint.24

- Tendon attachments include the FPL tendon and EPL tendon, which inserts on the epiphysis of the distal phalanx.

- The pediatric thumb distal phalanx is further stabilized by fibrous septae in the pulp of the finger and ulnar and radial lateral interosseous ligaments between the base and tuft.

Incidence and Related injuries/conditions

- Metacarpal and phalangeal fractures account for about 21% of all pediatric fractures, and the phalanges are the most commonly injured bones of the hand in this population.1,11

- The annual incidence of phalangeal fractures in children and adolescents up to 19 years old is approximately 2.7%.25

- In the pediatric population, the little finger is the most commonly fractured digit, followed by the thumb.3,4,26

- In one study, the incidence of thumb fracture was found to be low in children under the age of 10, but a steep rise was noted after this age, with the thumb becoming the second most commonly fractured ray in adolescents.3

- In the thumb, the proximal phalanx (52%) was fractured more frequently than the metacarpal (31%) and distal phalanx (17%).3

- In one study on the incidence of distal phalanx fracture distribution across the digits in children, the thumb accounted for 25% of all fractures and ranked second behind the middle finger. Of these, Salter-Harris type I and II fractures were most common, followed by tuft and shaft fractures, respectively.5

- The incidence of all phalangeal fractures is highest in children aged 10-14 years, which coincides with the time that most children begin playing contact sports.1

- Despite the fact that most patients are right-hand dominant, the distribution of phalangeal fractures is generally found to be similar in both the right and left hands.3,26

- Physeal injuries account for 15-30% of all pediatric fractures, and significant growth disturbance may occur in approximately 10% of cases. These types of injuries are most common during the adolescent growth spurt between ages 10-16, and are more common in boys than in girls.26

- Salter-Harris II fractures have been shown to have an incidence of 39% of hand fractures overall, and they represent approximately 90% of all Salter-Harris fractures in the hand.27

- IP joint dislocations are uncommon injuries in the pediatric population.28